Understanding combustible dust standards and how they apply

By Tony Supine and Mike Walters

Three key entities are involved in combustible dust issues, each with its own area of responsibility:

NFPA: The National Fire Protection Association sets safety standards, amending and updating them on a regular basis. When it comes to combustible dust, several different documents come into play.Together, these standards define what it takes to prevent an explosion, vent it safely and ensure that it won’t travel back inside a building. Most insurance company policies and local fire codes state that NFPA standards shall be followed as code. Exceptions would be where the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ), such as Factory Mutual, specifies an alternative safety approach which might be even more stringent.

OSHA: It is Occupational and Safety and Health Administration’s role, together with local authorities, to enforce the standards published by NFPA. In the aftermath of the Imperial Sugar Company explosion in 2008, which killed 13 workers and injured 42 others, OSHA reissued its 2007 Combustible Dust National Emphasis Program (NEP) outlining policies and procedures for inspecting workplaces that create or handle combustible dusts. As defined by OSHA, “These dusts include, but are not limited to: metal dust such as aluminum and magnesium; wood dust; coal and other carbon dusts; plastic dust

and additives; bio-solids; other organic dust such as sugar, flour, paper, soap and dried blood; and certain textile materials.” The revised NEP, which OSHA reissued on March 11, 2008, was designed to ramp up inspections, focusing in particular on 64 industries with more frequent and serious dust incidents.

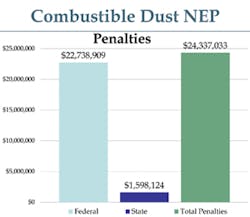

According to an October 2011 OSHA update on its Combustible Dust NEP, since the commencement of inspections under the 2008 program, more than 2,600 inspections have occurred. More than 12,000 violations were found during this time frame, including more than 8,500 that are classified as serious. Federal penalties and fines for these violations have totaled nearly $23 million, with another $1.6 million in state fines. OSHA uncovered a variety of dust collection violations in these

inspections, including dust collectors that were not equipped with proper explosion-protection devices and systems that were not vented to safe locations.

CSB: The U.S. Chemical Safety Board is an independent federal agency responsible for investigating industrial chemical accidents. Staff members include chemical and mechanical engineers, safety experts and other specialists with chemical industry or investigative experience. The CSB conducts thorough investigations of explosions — sifting through evidence to determine root causes and then publishing findings and recommendations. The CSB has a wealth of information on their website (www.csb.gov), including educational videos depicting how combustible dust explosions occur.

The CSB has become an outspoken advocate of the need for more stringent combustible dust regulations and enforcement. On Feb. 7, 2012, the fourth anniversary of the Imperial Sugar explosion, the chairman of the CSB issued a statement in which he applauded the progress made to date in dealing with combustible dust issues. He noted, however: “Completing a comprehensive OSHA dust standard is the major piece of unfinished business from the Imperial Sugar tragedy…. We believe such a standard is necessary to reduce or eliminate hazards from fires and explosions from a wide variety of combustible powders and dust.” The CSB also recommends that the International Code Council, which sets safety standards that are often adopted by state and local government, revise its standards to require mandatory compliance with the detailed requirements of the various NFPA standards relating to combustible dust.

Some members of Congress are also advocating faster action by OSHA to implement a combustible dust standard. In February 2011, Representative George Miller of California, together with co-sponsors John Barrow of Georgia and Lynn Woolsey of California, re-introduced a bill titled The Worker Protection against Combustible Dust Explosions and Fires Act (H.R. 522). If enacted, it would require OSHA to issue an interim standard within one year of passage and the Secretary of Labor to issue a proposed rule 18 months later, with a final rule due within another three years. At the time of this writing, there has been no vote on H.R. 522. A similar bill passed the House in April 2008 but never went to the Senate.

Relevant NFPA standards

Depending on the nature and severity of the hazard, NFPA 654 will guide you to the appropriate standards for explosion venting and explosion prevention, as follows:

NFPA 68 – Standard on Explosion Protection by Deflagration Venting: focuses on explosion venting — i.e., on devices and systems that vent combustion gases and pressures resulting from a deflagration within an enclosure, for the purpose of minimizing structural and mechanical damage. The current edition, published in 2007, contains much more stringent requirements than past editions, essentially elevating it from

a guideline to a standard.

NFPA 69 – Standard on Explosion Prevention Systems: covers explosion protection of dust collectors when venting is not possible. Methods for prevention of deflagration explosions include: control of oxidant concentration, control of combustible concentration, explosion suppression, deflagration pressure containment and spark extinguishing systems.

The general document, NFPA 654, also directs the reader to appropriate standards for specific manufacturing industries. The NFPA recognizes that different industries and processes have varying requirements, and it relaxes or tightens some aspects of its dust standards accordingly. Wood dusts, for example, tend to contain high moisture content that make for a potentially less explosive environment, resulting in a less stringent overall standard for that industry. Conversely, metal dusts can be highly explosive and subject to more vigilant regulation.

Common industry-specific standards

NFPA 61 – Standard for the Prevention of Fires and Dust Explosions in Agricultural and Food Processing Facilities: for facilities engaged in dry agricultural bulk materials including grains, oilseeds, agricultural seeds, legumes, sugar, flour, spices, feeds and other related materials; facilities that manufacture and handle starch; seed preparation and meal-handling systems of oilseed processing plants not covered by NFPA 36, Standard for Solvent Extraction Plants.

NFPA 484 – Standard for Combustible Metals: for all metals and alloys in a form that is capable of combustion or explosion, and outlining procedures used to determine whether a metal is in combustible or noncombustible form. It also applies to processing or finishing operations that produce combustible metal powder or dust such as machining, sawing, grinding, buffing and polishing.

NFPA 664 – Standard for the Prevention of Fire and Explosions in Wood Processing and Woodworking Facilities: establishes the minimum fire and explosion prevention requirements for facilities that process wood or manufacture wood products using wood or cellulosic fibers, creating wood chips, particles or dust.

Using performance-based codes

In 1995, the NFPA created a Performance-Based Support Team to assist NFPA technical committees with the transition to performance-based documents. Since then the NFPA has been incorporating performance-based options into its updated standards. The NFPA 654 general dust document first adopted this concept in 2006, with the other more specific combustible dust standards following suit since.

The NFPA uses relatively conservative textbook calculations in its standards for explosion protection equipment, and justifiably so. However, using performance-based codes, the NFPA also allows real-world destructive test data to be used in place of its own standard calculations, provided the dust collection supplier can provide adequate data to prove that the collection system is designed to meet a specific set of criteria for a given situation.

The use of real-world destructive test data is thus a permissible and sometimes overlooked approach. Find out if your dust collection supplier can provide real-world data to assist in a strategy that may help you to avoid over-engineering and save on equipment costs without compromising safety.

Tony Supine has held numerous positions with Camfil APC including research and development manager, technical director and currently plant manager. Mike Walters, a registered Professional Engineer with 30 years’ experience in air pollution control and dust collection systems, is a senior engineer with the company. Camfil APC is a leading manufacturer of dust collection equipment. The authors can be reached at 800-479-6801 or 870-933-8048; email [email protected].

This article originally appeared in the August 2012 issue of Processing Magazine.