It appears that El Niño effects are here, or at least that’s what many pundits predict. Pacific Ocean temperature levels have been rising and appear to be equivalent to those in the 1997 to 1998 period when the largest El Niño event on record occurred, leading to record precipitation throughout the Western U.S.

While this will potentially bring much-needed rain to drought-stricken regions of the country, many factors suggest water delivery and treatment systems will continue to face short- and long-term challenges.

In the short term, excessive precipitation will likely lead to mudslides and floods, particularly given the parched conditions that have persisted over the past four years. Extensive periods of drought and record wildfires have left landscapes charred, dry and barren, making mudslides more likely. In addition, stormwater will impact wastewater treatment facilities where combined sewer overflow systems exist, increasing the chances of illness from waterborne diseases. From here, boil notices should be instituted to protect communities from the contamination of raw water sources.

Mudslides and floods can also lead to significant property damage and loss of life. During the 1997 to 1998 El Niño event, it is estimated that property and other losses exceeded an estimated $1 billion, and more than 100 people lost their lives. With a longer period of drought preceding this year’s El Niño, along with an increase in population over the past 18 years, the chances are good for even greater destruction from powerful winter storms.

El Niño and municipalities

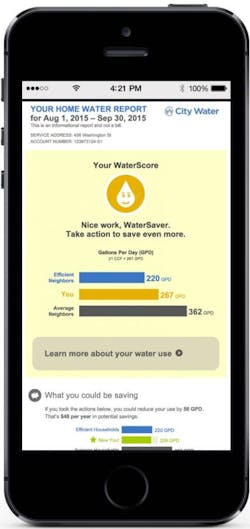

Another view of a water management tool

If predictions of a "Godzilla El Niño" come to pass, what does that mean for water utilities? When it comes to weather on planet earth, it is a zero-sum game. If more rain or snow is present in one part of the globe, less will occur in another because it is a closed system and the amount of water on the planet is essentially fixed. This will probably cause dramatic floods in southern California but worsening drought conditions throughout the Pacific Northwest because that region sees below average levels of rain and snow.

Another critical factor will be temperature levels and how they impact snow pack. Much of California’s water is stored in the form of high mountain snow that gradually melts throughout the spring and early summer, metering out water gradually as precipitation abates. If warming trends and decreased snowpack levels continue as forecasted, larger volumes of rain will cause significant problems in the short term but still leave the region thirsting for water as the summer irrigation season of 2016 peaks.

Groundwater concerns

While reservoirs may be largely replenished from above average levels of precipitation, people have increasingly relied on ancient groundwater reserves to supply agriculture and urban water needs. California, for example, relies on groundwater for up to 60 percent of its demand, up from 40 percent during times prior to the ongoing drought.

While underground aquifers recharge during wet periods, fossil reserves have been drafted at unprecedented rates, drawing water out much faster than they can naturally replenish. The Colorado River Basin is a good example of how dramatic this over-drafting is. From 2004 to 2013, the basin was reduced by an estimated 65 cubic kilometers, 75 percent of which was groundwater. This is equivalent to two Lake Meads, the largest reservoir in the U.S. The Ogallala aquifer, which runs from Nebraska to Texas in the Midwest, has dropped more than 15 feet in the past 10 years. At this rate the aquifer may contain just 30 percent of its current water reserves in as few as 50 years.

Many municipal water utilities rely on groundwater as their primary drinking sources, and it is becoming more difficult and expensive to draw on these sources that are further underground and require greater pumping energy to move. In addition, as deeper wells are drilled, greater concentrations of salt, selenium, boron, arsenic and other naturally occurring toxins are found that need more treatment to be made potable. This further increases costs and puts water supplies at risk.

What would a powerful El Niño mean for the drought and conservation efforts throughout the region? A consensus exists that even if the coming winter brought up to 200 percent of normal precipitation, it would not relieve the region from the gripping drought conditions of the past four years. Additionally, a long winter of rain will leave residents with the impression that conservation efforts are no longer needed. Combined with lower forecasted snow pack levels, this will leave people in a similar position next summer as they were in during the past several years.

Utilities can act

Knowing all of this, what can water utilities across the country do about these challenges, regardless of whether they are located in wet or dry regions? A few prescriptions can mitigate some of the negative impacts of El Niño while anticipating the long-term needs for continued water-use efficiency:

- Recognize that excess water will cause problems and begin proactive engagement with customers on mitigation programs. Many states have grant programs or other incentives for storm barrel, permeable surface and cistern installation to help address potential stormwater overflows.

- Build a database of email and phone numbers for rapid response communications. If a need to warn customers about storm system overflows, treatment system failures, boil notices or emergency maintenance arises, the ability to easily and quickly deploy mass personalized notifications can go a long way to reduce harm and build trust.

- Continue to educate consumers on the value of water, the utility’s efforts to ensure high-quality and reliable service, and the long-term need to continue to improve water use efficiency. This will lead to more resilient systems and reduce costs for customers and utilities while building the political capital needed to make future infrastructure investments.

While El Niño may bring some much-needed rain to certain areas of the country, it also delivers excessive, unneeded precipitation to other areas. Regions used to a given amount of water will receive less and be faced with mounting water stress in the future.

This also creates an opportunity. In light of an increasingly unpredictable wet-dry spectrum, the partnership between utilities and end users can be strengthened. WaterSmart would like to see them acknowledge the short-term and long-run reality and begin to engage in a brutally frank conversation on how to work together to address it.

As director of marketing, Jeff Lipton manages WaterSmart Software’s go-to-market strategy development and marketing campaign activities, along with sales operations support. He earned a Master of Business Administration from the Haas School of Business at the University of California. Lipton also received a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Colorado. He may be reached at [email protected].