Process historians enable digital transformation

Digital transformation is a goal for all process plant operators worldwide because of the benefits delivered in terms of greater throughput, improved quality, reduced maintenance expenses, lower energy use and other operational improvements.

The first steps toward digital transformation are digitizing as much plant data as possible, and then storing this data where it can be easily and securely accessed by different software platforms, each of which are used to improve plant operations.

Much of the desired data is already digitized using various sensors, instruments and analyzers. Other data can be digitized by converting manual pen-and-paper data entry methods to more automated procedures. Ideally, these procedures can be fully automated such that data flows directly to a storage system, but partial automation where data flows from handheld tablets to a storage system is another possibility.

As mentioned, improving plant operations by means of making the right data available to various software platforms is the goal. These software platforms include the basic process control system (BPCS), asset management software, maintenance management software, enterprise resource planning systems and others. Here are the main options for storing the digitized data produced by these software platforms.

Data storage options

Relational databases are widely used in all sorts of non-production applications by most process industry companies, but they have many drawbacks for storing digital data from process plants.

A relational database must be preconfigured for each possible field, along with designated relationships among all fields. Given the wide variety and complexity of process plant digital data, this is a problematic step. Even if this step can be accomplished — and continuously maintained as new data is added — relational databases will often suffer severe performance degradation as the amount of stored data increases, primarily because every additional data point requires a new record. Due to these and other issues, many process plants have started out with relational databases, only to seek an alternative more suited to their needs.

The preferred alternative is a process historian as it is specifically designed to efficiently store historical data over long periods of time. These types of databases store continuously monitored process plant data such as flows, pressures, level and temperatures — and are therefore capable of handling the types of data typically produced by processes, units and procedures. Their data storage capabilities are prodigious, making them suitable for even the largest plants, those continuously historizing hundreds of thousands of data points daily. Many process historians come with built-in tools for analyzing and presenting data, a point explored in detail later in this article.

Process historians also come with the interfaces required for secure connection to the other software platforms, in particular OPC UA.

Secure connectivity

The OPC Classic protocol has traditionally been used to exchange data between process historians and other industrial automation software platforms. Originally, OPC was an acronym for OLE for Process Control, and it is a software interface standard that allows Windows programs to communicate with industrial hardware devices and systems. OPC is implemented in server/client pairs, and the OPC server is a software program that converts the hardware communication protocol used by a device or system client into the OPC protocol.

The OPC Unified Architecture (UA) is a newer development, inheriting the benefits of earlier OPC technologies and adding significantly enhanced communication efficiency and security. In this iteration, OPC is an acronym for Open Platform Communication. Its effectiveness and widespread adoption by many industrial automation vendors has made OPC UA an essential technology for data exchange among software platforms (Figure 1).

Among automation vendors, Yokogawa has been a long-time supporter and a member since the establishment of the OPC Foundation, contributing to the formulation of all OPC specifications, from OPC Classic to OPC UA. This participation ensures Yokogawa’s process historian is fully compatible with OPC UA, providing built-in and secure connectivity to a wide variety of software platforms.

The right historian supports digital transformation initiatives by gathering large volumes of plant data and transforming it into usable, high-value business information. It should include extended OPC UA connectivity to best enable more efficient and secure communication with business systems and data analysis tools to help achieve operational improvements.

Although OPC UA is widely used to provide secure communications among products from different vendors, there are advantages to using the same vendor for various software platforms, particularly the process historian and the BPCS.

Third-party vs same-vendor historians

A third-party historian is defined as any process historian supplied by a different vendor than the one used for the plant’s BPCS. Although using third-party historians for process plants is a common practice, there are advantages to using the same vendor for the process historian and the BPCS.

As compared to a third-party historian, a same-vendor historian will typically synchronize automatically with the BPCS, simplifying setup. This synchronization can be re-executed at any stage to align the two systems after BPCS changes.

Bulk graphics conversion between the historian and the BPCS is supported with a same-vendor solution and will be much faster than the manual conversions often required with third-party solution. BPCS graphics can usually be replayed within the historian to show historical events in real-time, aiding review of past incidents and training. The BPCS can typically scan and import historical trend groups for immediate use because the supporting tag templates are created automatically.

With a same-vendor solution, BPCS and historian configuration will be seamless, with a unified user interface created using the same graphic engine and configuration tools. This provides significant benefits, such as reduced initial engineering and minimized ongoing maintenance time, simplified training requirements, lower cost of ongoing ownership and easier migration and upgrade paths.

One same-vendor solution provides retention of data precision in its historian because it does not use data compression to store process data, as is typical with third-party historians. Because there are no compression parameters to set, this results in less required upfront configuration and ongoing maintenance.

The historian supplied with this same-vendor solution calculates and stores process continuous aggregations (minimum, maximum, mean, summation, standard deviation) on the fly, each of which can be quickly retrieved from storage by the BPCS. This provides a superior response time when compared to a typical third-party historian, which must extract all process data in the required time/date range to calculate aggregations on demand from the BPCS. Discrete aggregations, used to count the number of times equipment (such as pumps or motors) are turned on and equipment run time for example, can also be quickly supplied.

Turning data into information

The data handling and presentation tools supplied with process historians vary significantly from one vendor to the next. Providing these tools within the historian eases digital transformation because digitized data stored within the historian can be readily viewed, analyzed and shared using native features, as opposed to requiring data exchange and integration with other software platforms.

The vast amounts of raw production data stored in a typical historian must be studied and analyzed to transform it into valuable information, preferably using built-in tools and applications. For example, alarm reporting and analysis is an effective tool for evaluating alarm system performance. KPIs and reports built into the process historian software measure and identify alarm information. This includes how many alarms are generated daily, how many alarms are handled by operators each hour and any deficiencies in the control system.

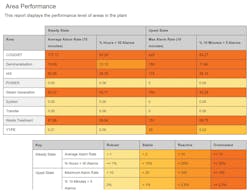

Detailed reports (Figure 2) help users measure the effectiveness of the alarm system. Automated distribution of these reports via email ensures this information is made available across the organization to support improvements in the stability and safety of plant operations. In addition, customized reports enable users to perform deeper investigations to address specific concerns in the alarm system.

Leading benefits of alarm reporting and analysis include:

- Safer and more productive operations through reduced risk of safety-related incidents and shutdowns

- Operational improvements gained by identifying opportunities through KPI examination

- Faster reaction by operators to abnormal situations

- Improved alarm information via enhanced analysis in customized reports and improved data visualization

Safety function monitoring

Plant owners must ensure safety systems are maintained throughout the operational lifespan of a process plant. To provide this and other capabilities, safety function monitoring is another tool often integrated within a historian. It is used to automatically collect, organize and present all safety-related data from a safety instrumented system (SIS) to conveniently measure safety system performance.

Data is compared against the actual operational safety function activity to highlight a SIS exceeding expected design targets or underperforming. Standardized reports are available to document any evidence relating to ongoing performance of the safety system, and to maintain an evidence trail that satisfies safety standards.

Key benefits of a historian with safety function monitoring tools include:

- Quick identification of safety events such as safety instrumented function activations, overrides/inhibits and protection layer availability

- Benchmarking of safety performance against design expectations using performance data from actual operation

- Reduced risk by identification of issues not recognized in the safety design

- Ensuring the safety system is performing as designed

- Upholding the overall consistency of safety system information throughout the safety lifecycle

Alarm reporting and analysis, and safety function monitoring, are just two examples of the types of tools provided with modern historians to aid digital transformation initiatives.

Conclusion

Digital transformation initiatives require ready access to digitized data, best handled by a process historian instead of a relational database. Secure connectivity to the historian allows different software platforms to exchange data, typically using the OPC UA protocol. If the same vendor is used for both the historian and the BPCS, benefits are realized through closer integration between the two platforms. Modern historians come with a host of built-in tools to quickly and easily turn stored data into actionable information.

Nick Cross is a marketing executive with Yokogawa Marex and he has 18 years of experience within digital, marketing and sales environments. He joined the marketing team at Yokogawa Marex in 2015 and helps develop, promote and support specialist software and IT solutions for process information management in production facilities, such as oil refineries and chemical/petrochemical plants, across the globe.

Ma Haoran works in system product planning with Yokogawa Electric Corporation. He is responsible for software and DCS solutions support, and sales and marketing at Yokogawa’s headquarters in Tokyo. In this role, he handles customer business and operational consultation, and also supports global MES sales, marketing and business promotion.